In this note, we look at the possibility that Australia will experience a recession, including potential external or domestic catalysts. The external factors examined include a US recession induced by higher interest rates or on account of an escalation in banking sector concerns. The domestic trigger for a downturn might be the RBA taking interest rates well above levels currently being contemplated by the market. We find that the chance of a recession is higher than usual but it’s not a sure thing.

How likely is a US and Australian recession?

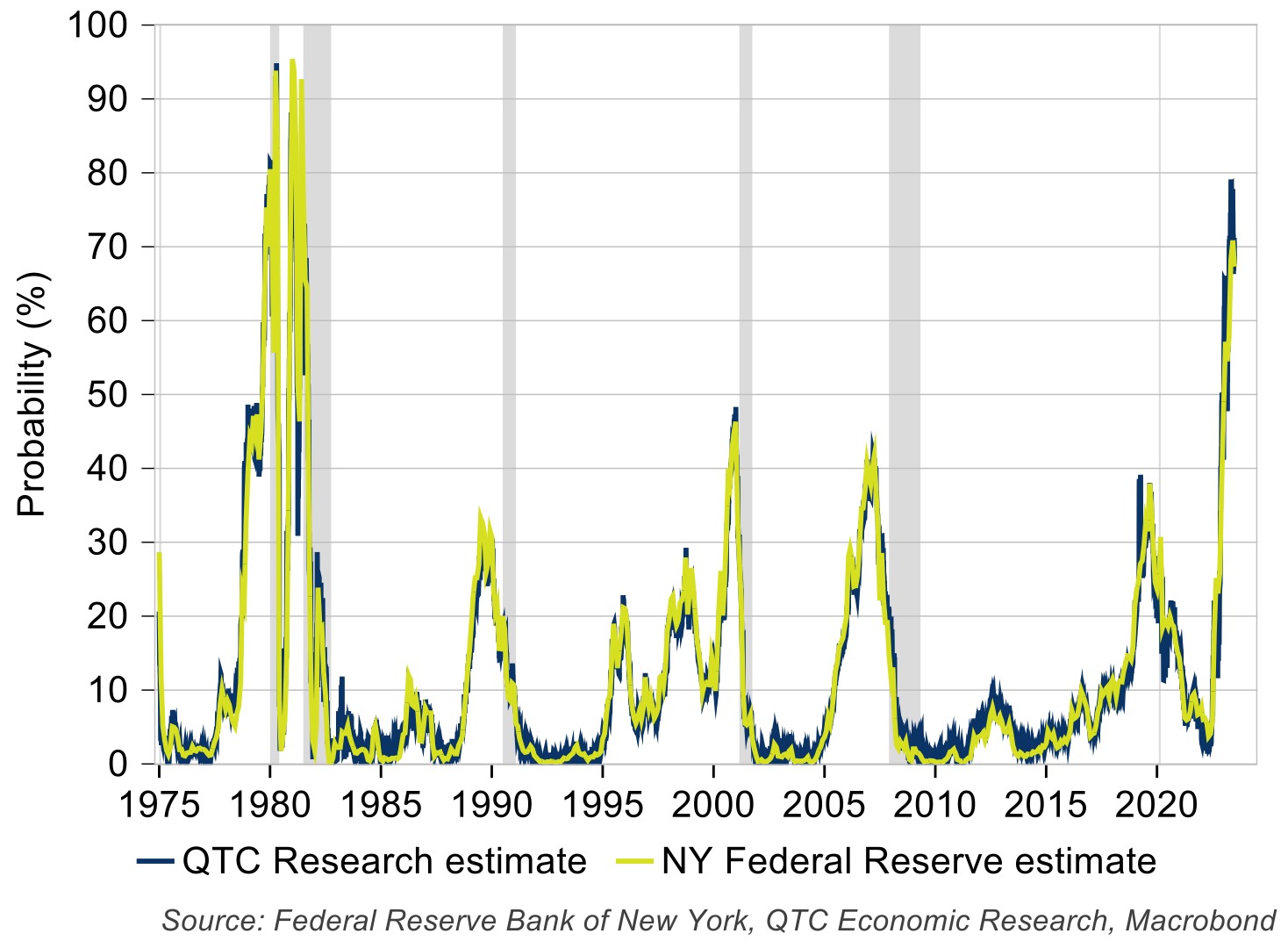

There is a high probability that the US will have a recession in the near future, with an update of our earlier work pointing to a 70 per cent chance of one in 12 months’ time (Graph 1). This is broadly consistent with the consensus from Bloomberg’s survey of economists (65 per cent) as well as estimates from the Federal Reserve Banks of New York (71 per cent) and Cleveland (78 per cent).

Graph 1: US recession probabilities

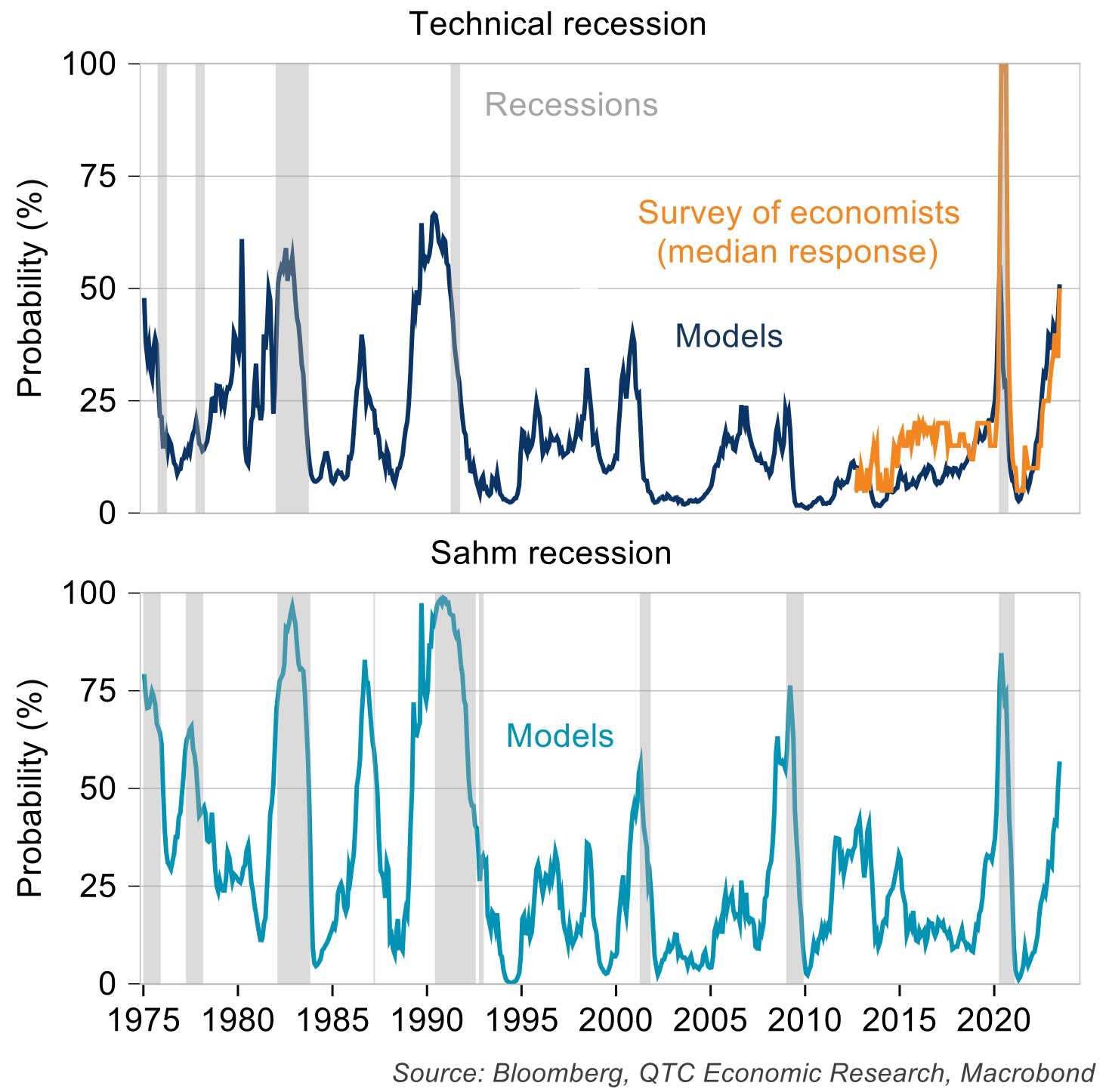

The risk of Australia experiencing a recession within the next 12 months has also started to increase more recently. Both our models as well as Bloomberg’s survey of economists suggest there is a 50 per cent probability of a ‘technical’ recession occurring sometime over the next 12 months.[1] This is well above the risk of recession that is normally observed, with this usually being around 10 per cent.

A potential issue with these sorts of estimates is that recessions have been few and far between in modern Australian history. Having fewer examples to draw on makes it more difficult to estimate when recessions might occur in the future. To address this issue, the RBA recently assessed whether Australia might experience a ‘Sahm recession’ (which occur relatively more frequently).[2] We estimate the probability of a Sahm recession to be higher than that for a technical recession, with a 60 per cent probability of it occurring within the next 12 months and an 80 per cent probability within the next 2 years. These results are similar to those from the RBA staff.

Graph 2: Probability of a recession in Australia within the next 12 months

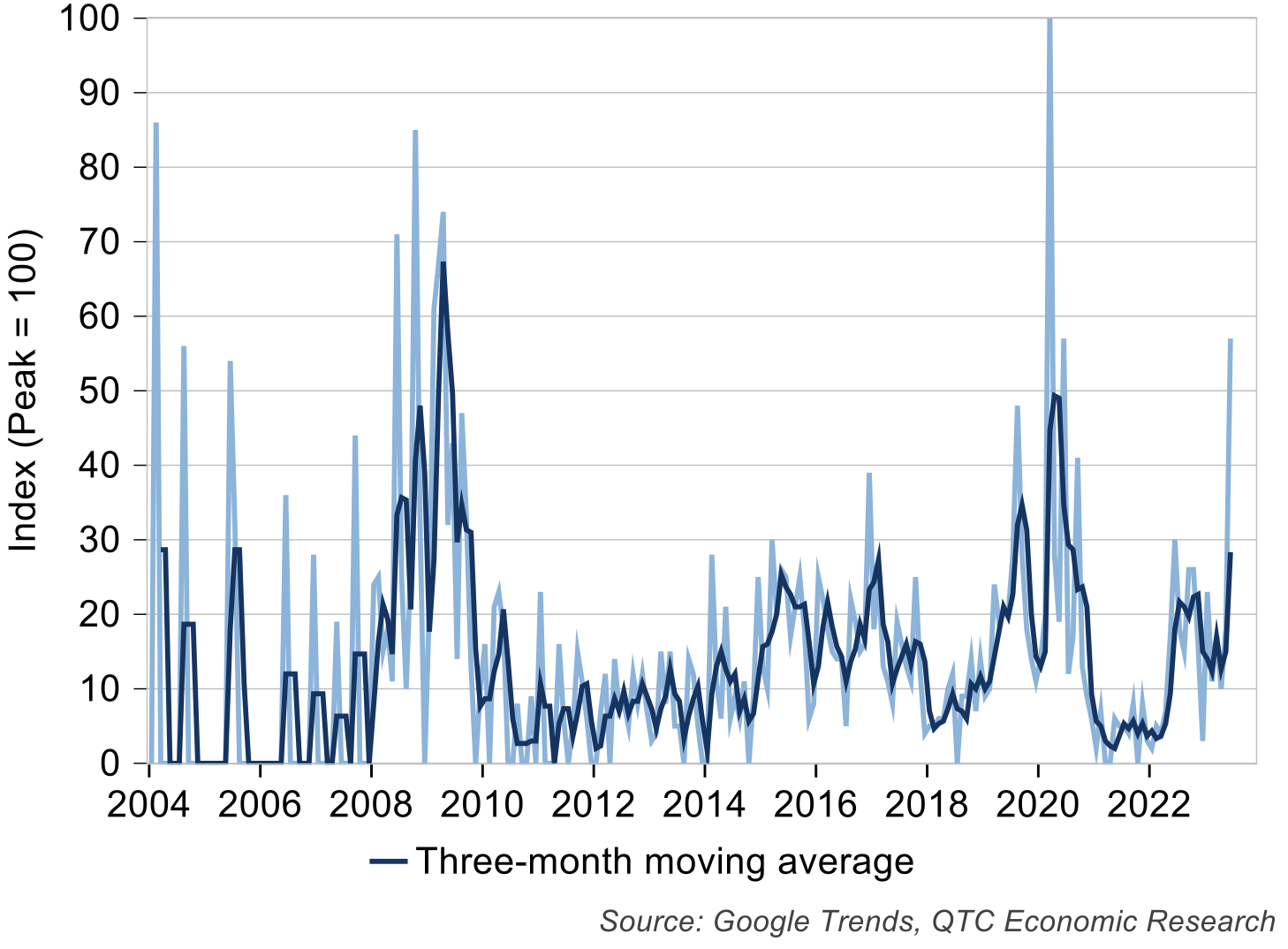

With expectations of softer future conditions, it is not surprising that the possibility of a recession is also being more widely contemplated by the broader community. Google search interest in an ‘Australian recession’ is at levels that have only been exceeded during the COVID-19 and the GFC periods (Graph 3).

Graph 3: Google search intensity for ‘Australian recession’[3]

If the US sneezes will Australia catch a cold?

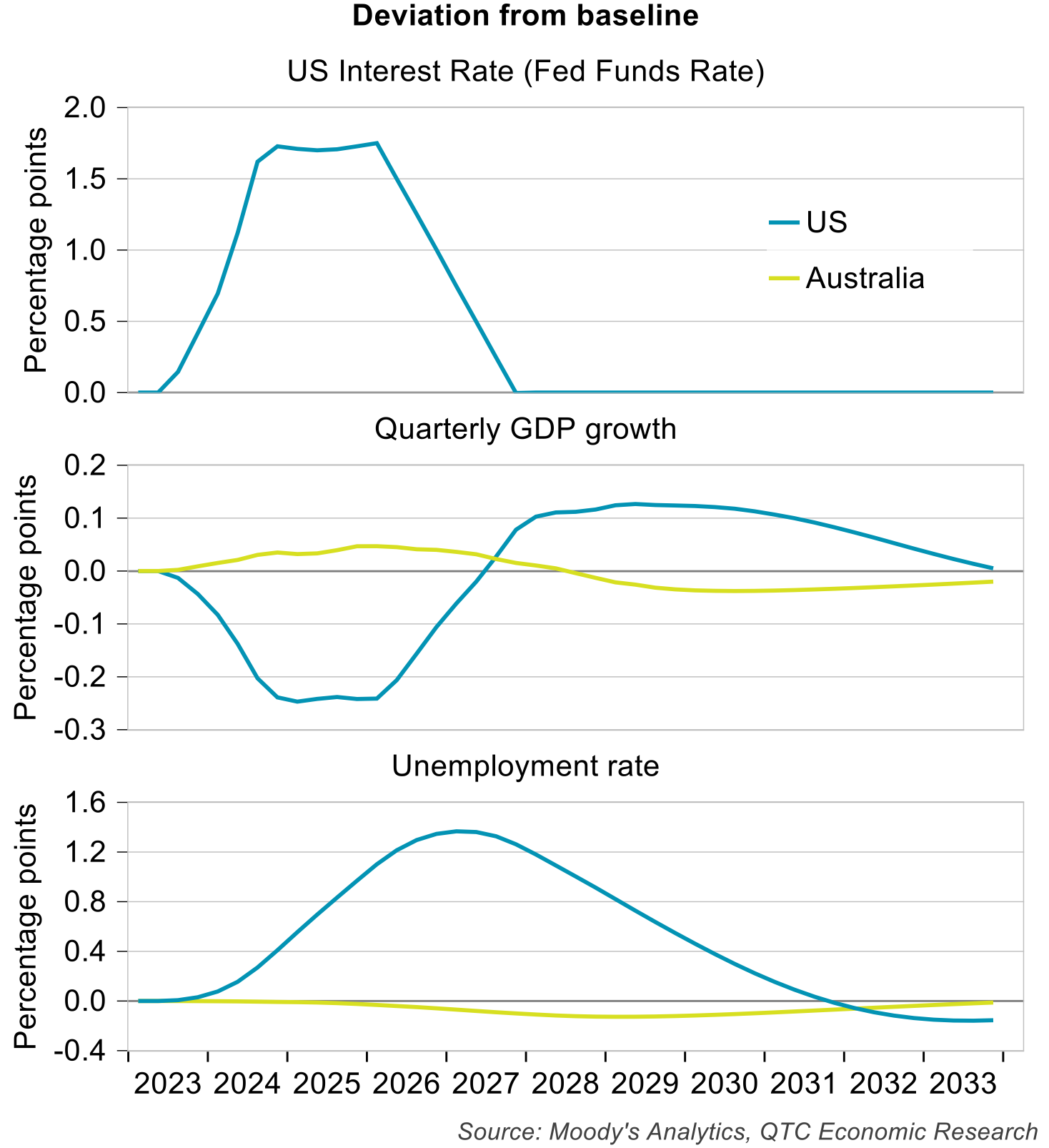

One reason for the high US recession probabilities is the substantial policy tightening delivered by the Federal Reserve (‘Fed’). This raises the question: if interest rates in the US were to be taken even higher, what impact might this have on both the US and Australian economy?

To answer this question, we conduct scenario analysis using Moody’s Analytics’ Global Macroeconomic Model. We assume that the Fed keeps rates higher for longer than currently expected by markets, in an attempt to contain actual and expected inflation.[4] This scenario sees US economic growth slow and the unemployment rate rise relative to the baseline scenario prepared by Moody’s Analytics (Graph 3). In both the baseline and alternate scenarios, the US economy avoids a ‘technical recession’ but it does experience one based on the Sahm Rule.[5]

In contrast, the Australian economy benefits from higher US interest rates. In this scenario, higher US interest rates lead to a depreciation of the Australian dollar relative to the US dollar.[6] The lower exchange rate provides a small boost to domestic GDP growth, which in turn sees the unemployment rate dip lower and inflation increase (Graph 4). These effects are very small though, which is not surprising given the size of the shock and that the Australian economy only has limited direct linkages to the US.

Graph 4: Impact of higher US interest rates compared to baseline scenario

What if the US is not in for a ‘typical’ recession induced by policy tightening? Instead, recent flare-ups in the financial sector suggest there is some possibility, however small, of a banking sector crisis. Were this risk to materialise the impact would be significant. In April, Moody’s Analytics’ economists constructed multiple scenarios related to this:

- Baseline – Policymaker actions limit further bank failures, though small- and medium-sized banks become more circumspect in their lending. The cumulative tightening of lending standards reduces the need for further hikes by the Federal Reserve with rates topping out mid-year at those ultimately observed (5 to 5.25 per cent).

- Crisis Continues – Further failures of small banks prompt depositors to quickly withdraw their savings (a ‘bank run’). This is not adequately responded to by authorities and leads to tighter financial conditions, falling confidence and the economy entering a severe recession in Q3 2023. Weaker economic conditions see lending standards tighten further, which affects conditions in commercial and residential property markets. This softening in the economy prompts the US Treasury and banking regulators to adjust policies to limit deposit outflow. The Federal Reserve plays its part by cutting interest rates aggressively to support the economy and enhancing liquidity provided to the financial system.

- Inflation Trumps Financial Stability – Concerns over financial institutions remain contained for a time but sticky inflation requires the Fed to take rates much higher than expected. This affects the value of bank assets which leads to more banks going under. An ad-hoc response leads to a run on banks by depositors, falling confidence and tighter lending standards. A severe recession results, albeit later than in the ‘Crisis Continues’ scenario.

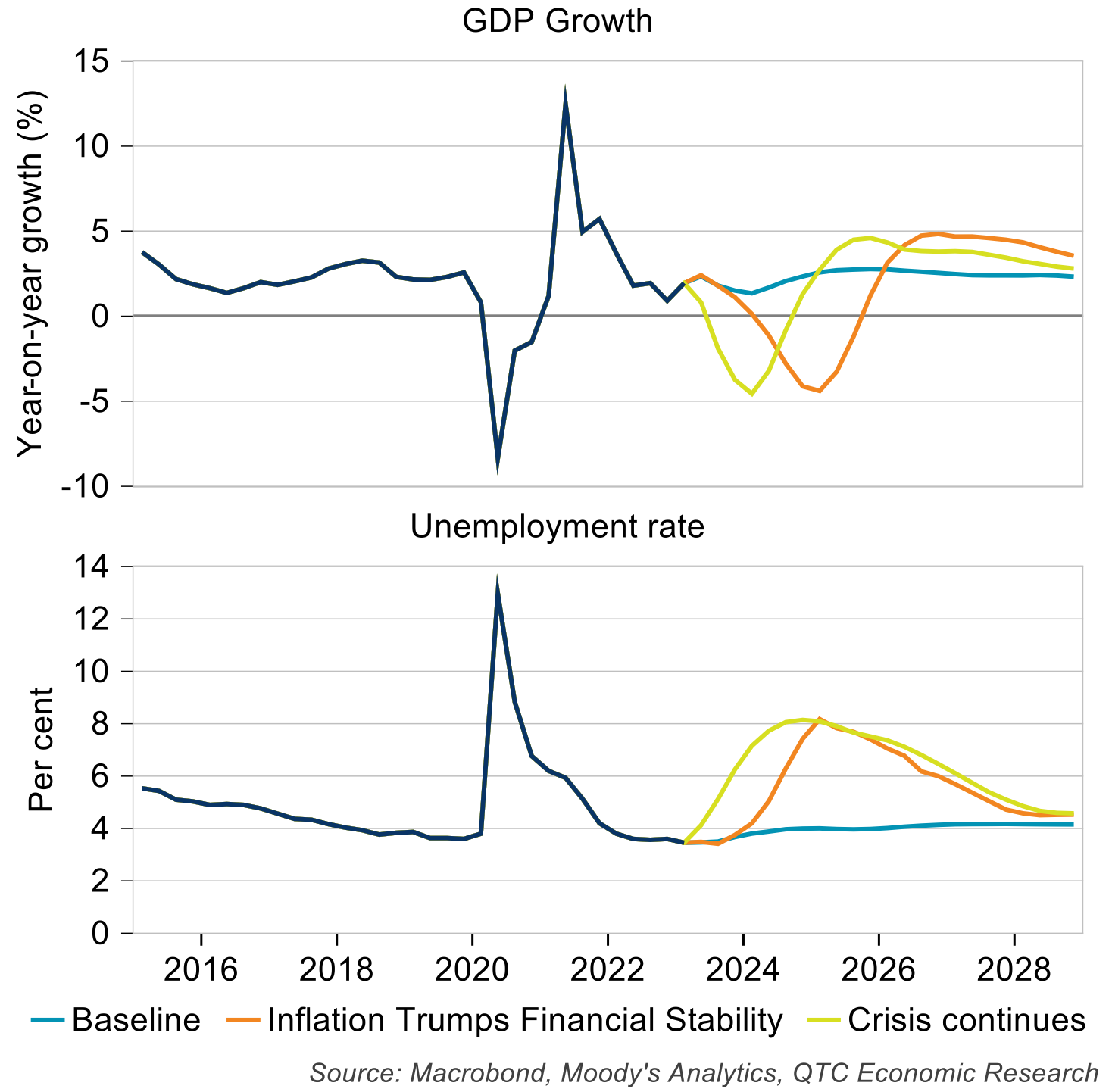

Moody’s Analytics’ Global Macroeconomic Model can be used to see how an escalation of US banking sector concerns might affect both the US and Australia. The impact on the US economy is significant with a deep recession the likely outcome in these alternate scenarios (Graph 5). The unemployment rate increases by four percentage points in both the alternate scenarios, which is larger than the typical increase in a recession without a banking crisis but is slightly less severe than the experience in the Global Financial Crisis (GFC).

Graph 5: Impact of US banking sector concerns on the US economy

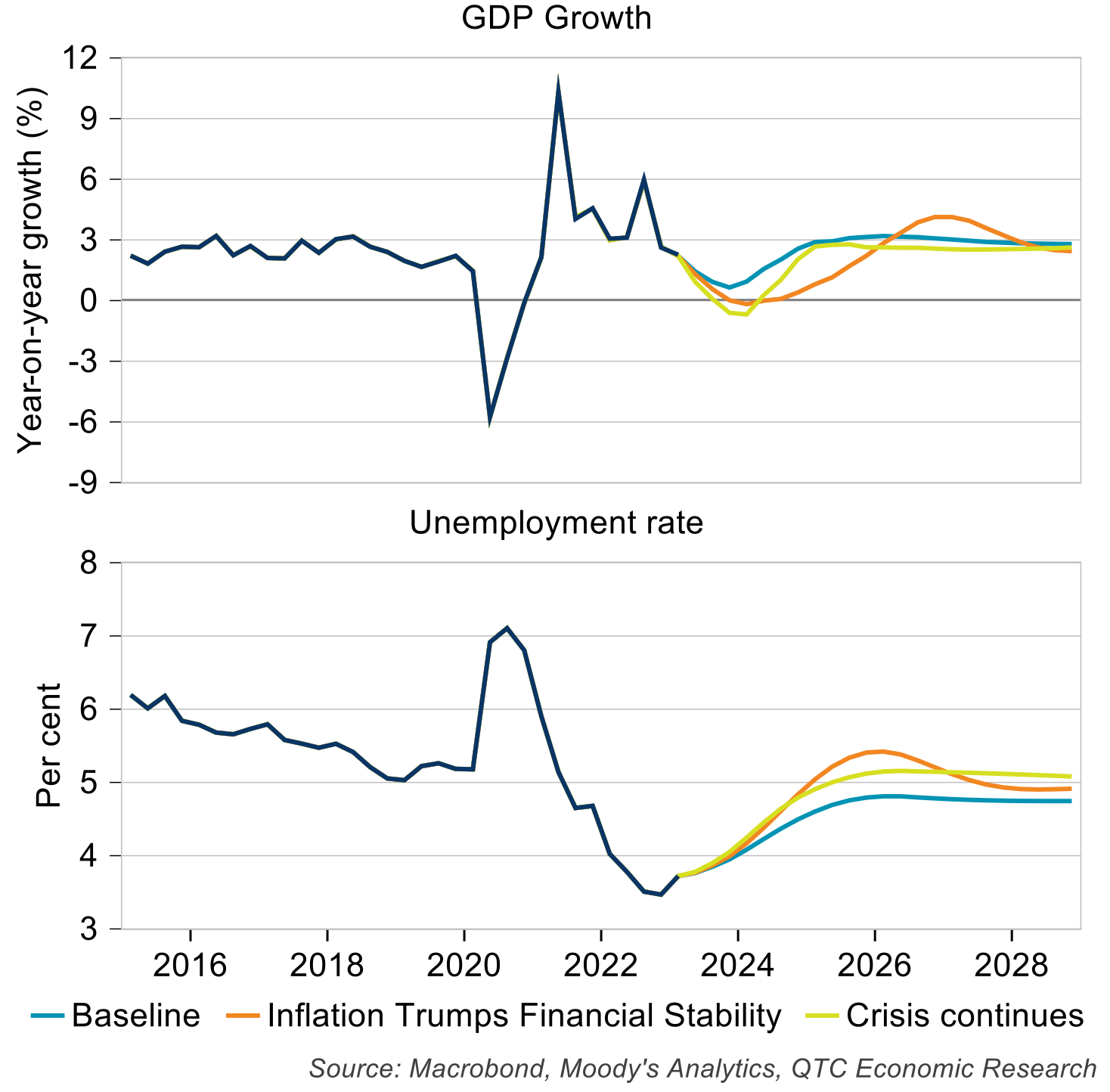

If conditions in the US financial system worsened there would be flow-on impacts to Australia (Graph 6). Moody’s Analytics’ Global Macroeconomic Model suggests these may include negative GDP growth (and a ‘technical’ recession) and the unemployment rate lifting noticeably above the baseline projection. Australia would therefore not be immune in this instance.

Graph 6: Impact of US banking sector concerns on Australian economy

The Answer Lies Within

Overseas events could prompt a slowdown in the Australian economy, with those related to the financial system likely to be more impactful. But absent this, what could the next phase of Australia’s economic cycle look like if domestic factors – such as even higher interest rates than presently anticipated – proved to be more meaningful drivers?

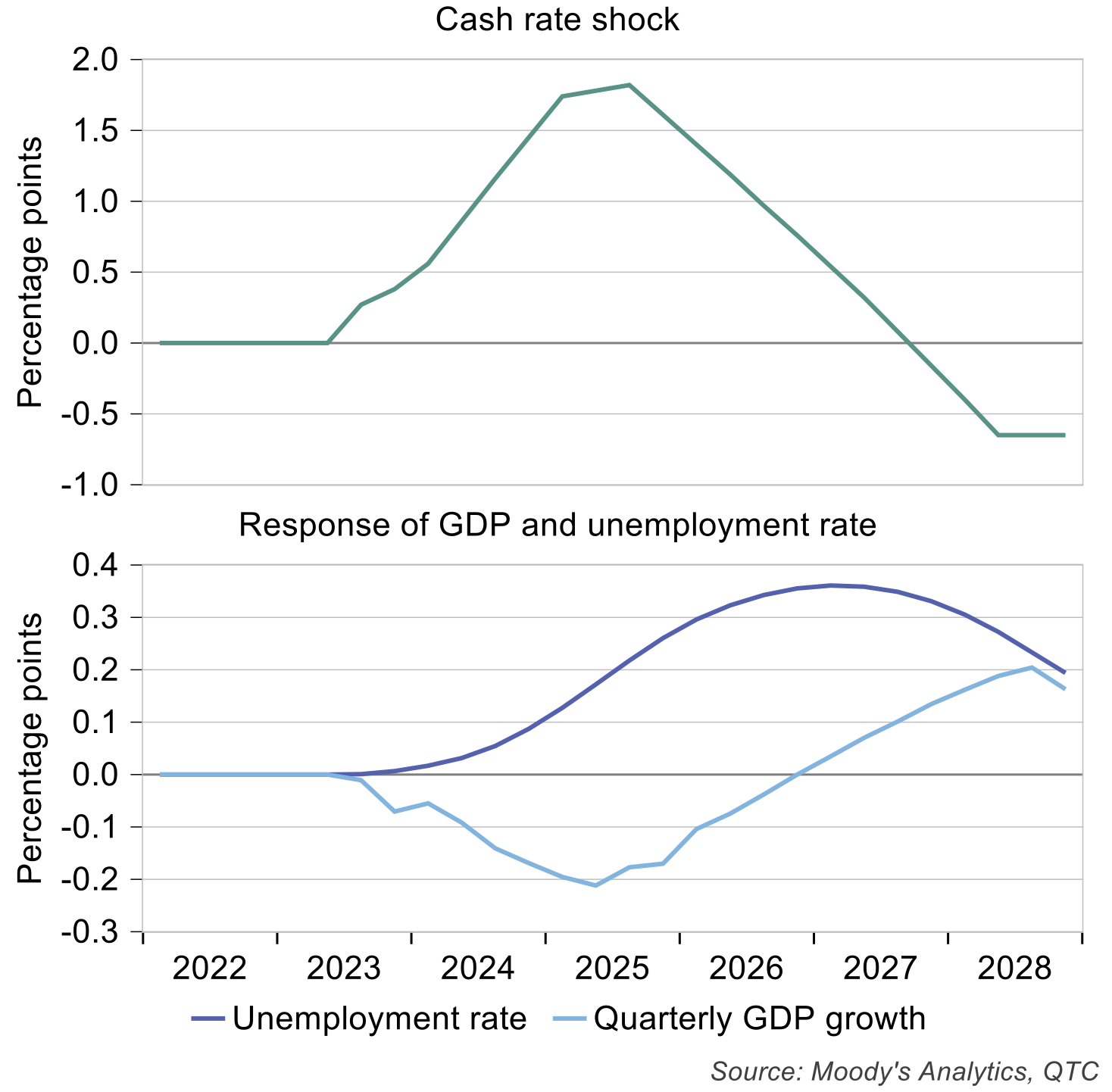

Market pricing has the cash rate increasing to around 4.5 per cent by the end of this year. However, an argument could be made that interest rates will need to increase beyond this to ensure a timely return of inflation to its target.[7] In this alternate scenario, the cash rate increases to around six per cent by Q1 2025. It is then assumed to be held there for six months before gradually declining thereafter.

This scenario sees GDP growth slow and the unemployment rate rise by more than in the baseline scenario (Graph 7). While Australia would still not be expected to experience a technical recession, the increase in the unemployment rate would be consistent with Australia experiencing a recession based on the RBA’s modified Sahm Rule.

Graph 7: Cash rate and unemployment rate forecasts under baseline and alternate scenarios

Recession suppression?

The model-based estimates point to a reasonable possibility that Australia experiences a recession in the period ahead. Similarly, some of the alternate scenarios presented suggest that a Sahm recession is not particularly far-fetched. Yet a recession here is far from a sure thing.

One reason why Australia may avoid a recession is that there is scope for policy to offset a downturn if one were to occur. Solid budget positions give governments capacity to provide additional support if needed. Interest rates are also now well above the zero lower bound, which would allow the RBA to ease policy in a downturn.

Demand and spending could also prove to be more resilient than expected. There continues to be solid population growth, while households (in aggregate) still have large savings buffers. There are also anecdotal reports that firms may ‘hoard labour’ even as demand softens after the last few years of very tight labour market conditions. And finally, conditions in the housing market appear to be bottoming out, which should alleviate some of the drag on household spending.

Implications

In this article, we aimed to shed light on what the next phase of Australia’s economic cycle might look like. A slowdown is underway, and this should gather pace over the period ahead. Getting a sense as to whether this slowdown might be so pronounced as to turn out to be a recession is more challenging. Recession risks are rising and, outside the pandemic, are as high as it has been since the early 1990s recession. Modestly higher interest rates from the Fed or RBA won’t lead to a recession but a dramatic re-escalation of US banking sector concerns or an unforeseen extension to the RBA’s interest rate hiking cycle might. A recession is not our central case at this time and there are reasons for optimism that the economy can navigate the narrow path ahead. Nonetheless, the risk of one is rising and it is very much a plausible outcome that is important to consider at the current time.

Footnotes

[1] A technical recession is defined as two consecutive quarters of negative GDP growth.

[2] The RBA staffs’ modified Sahm rule defines a recession as occurring when there was an increase in the quarterly unemployment rate of ¾ percentage point or more from its minimum over the previous 12 months. This definition of a recession appeared in analysis last year by RBA economists which highlighted model-based estimates of the probability of Australia being in recession by Q3 2024 as being between 65 per cent and 80 per cent.

[3] Google Trends measures the popularity of a search term relative to that of other searches. An index value of 100 corresponds to maximum interest in that search (relative to others) across the entire period of interest.

[4] The higher US interest rates scenario assumes that further interest rate increases are needed to provide the Federal Reserve with some additional confidence that core inflation will return to its two per cent target. In this scenario rates are assumed to peak at 5.75 per cent in Q1 2024 before being held there for all of next year and then declining by 0.25 percentage points per quarter over the following few years. The time at which rates were held at their peak and the pace at which they are lowered is consistent with the historical experience in recent decades.

[5] The Sahm Rule indicates the start of a recession when the three-month moving average of the unemployment rate increases by ½ percentage point or more from its minimum over the previous 12 months

[6] Specifically, an increase in US interest rates sees the return on US dollar assets increase relative to those in foreign currencies (including the Australian dollar). This contributes to stronger demand for the US dollar relative the Australian dollar which, in turn, leads to a depreciation of the exchange rate.

[7] Examples include the recent international experience with higher interest rates amid sticky services inflation, how restrictive policy settings had to be in previous instances when inflation here has been elevated, and the risk that higher inflation outcomes could become embedded in inflation expectations.