The strength of the economic recovery, coupled with a rise in global inflation, has seen an increased focus on the outlook for monetary policy in Australia. Indeed, even though the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) has suggested that cash rate hikes are unlikely this year, market-based measures suggest that this could occur as soon as mid-2022. Given these different views, in this note I examine different paths the cash rate could take during a policy tightening cycle, something we haven’t encountered for some time.

This is the first of a two-part series exploring the outlook for the cash rate. The second note will be released in the next fortnight and will discuss the long-term outlook for the cash rate. If you would like to receive an alert when this next piece is published, along with any of our other economic research updates, you can opt-in here.

Inflation and monetary policy

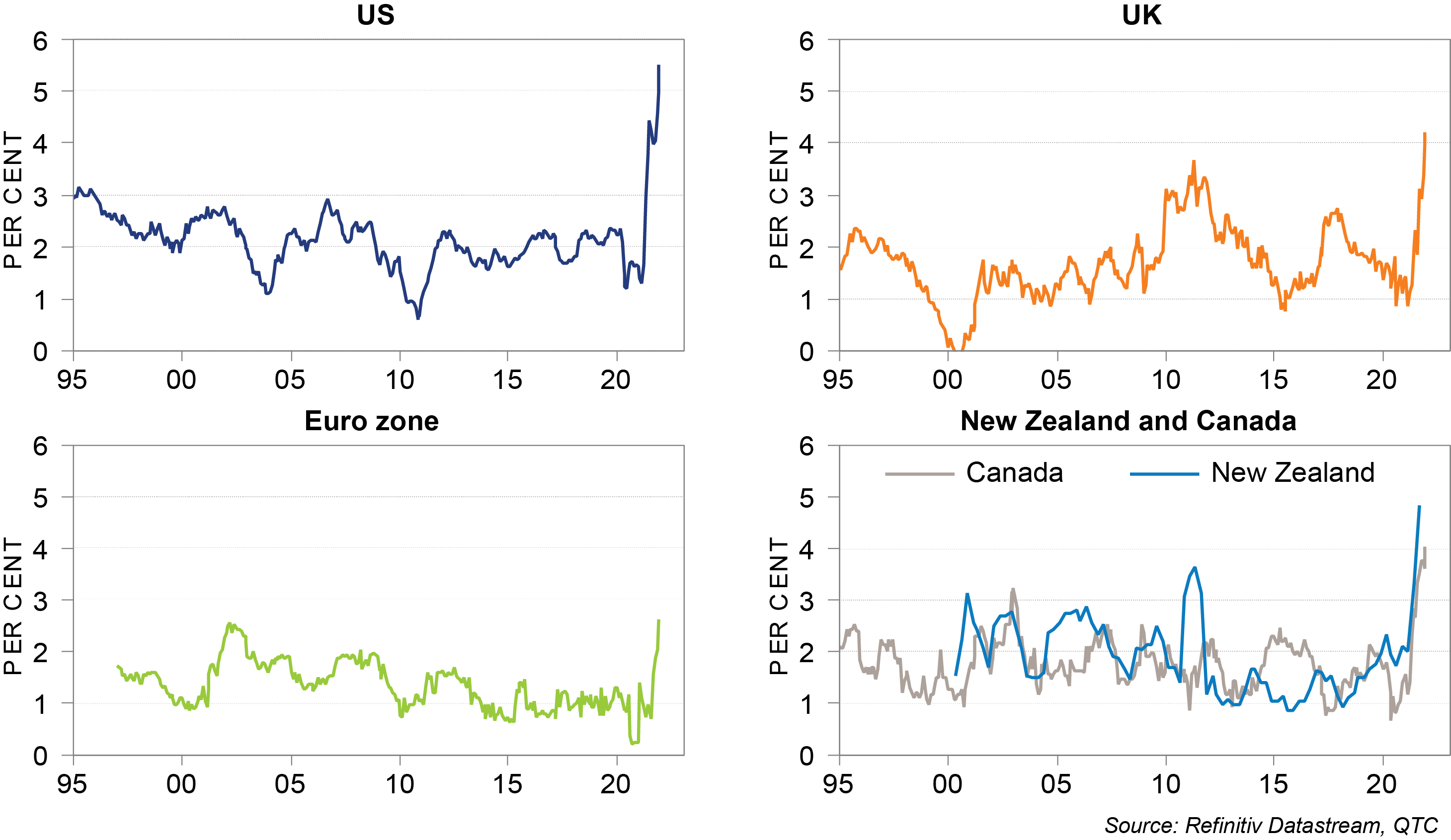

Underlying inflation has reached its highest level in around 30 years across a range of major developed economies (Graph 1). While some of these pressures should ease over the year ahead, there is a growing risk that inflation will prove to be more persistent than previously expected.

Central banks have responded to this evolving outlook by signalling a tightening of monetary policy. In terms of policy rates, the US Federal Reserve expects it will raise the Fed Funds Rate three times in 2022, while the Bank of England and Reserve Bank of New Zealand have already started to increase interest rates. The European Central Bank (ECB) has outlined a slower path to increasing rates, with ECB President Christine Lagarde noting that the first hike is unlikely in 2022, though markets expect that policy tightening could occur earlier than this.

Graph 1: Underlying CPI inflation

(CPI excluding volatile items, year-on-year growth)

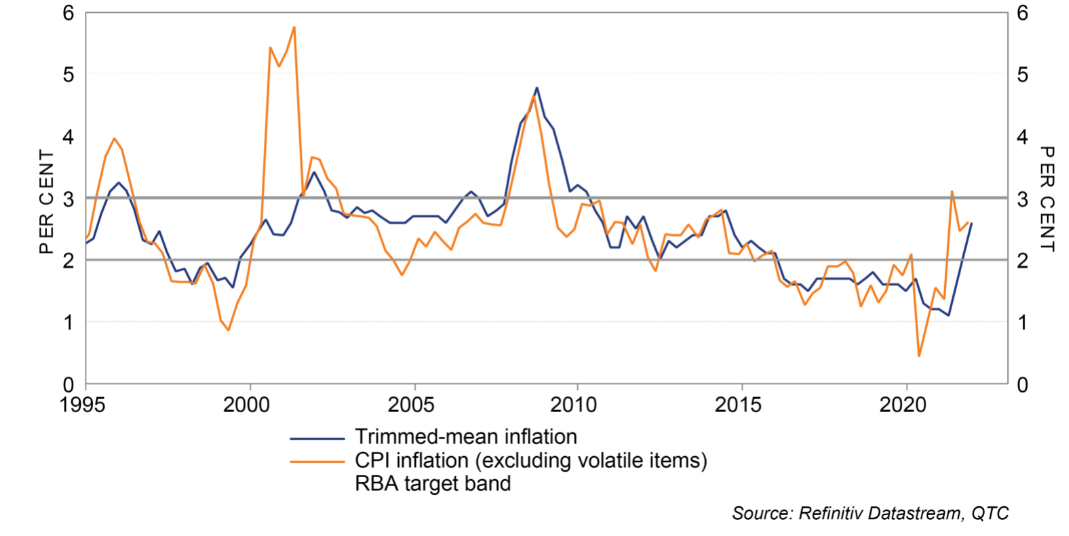

To-date Australia has experienced a more modest increase in underlying inflation relative to many other advanced economies (Graph 2). In its most recent commentary, the RBA argued that this more gradual increase should continue over the next couple of years, in part reflecting inertia in the wage-setting processes.

If this outlook is correct, then this could see the RBA lift its policy rate later (or more gradually) than some other major central banks. However, strong recent readings on the domestic labour market and inflation will see the RBA revise its outlook for inflation higher in next weeks’ Statement on Monetary Policy. A stronger outlook for inflation could in turn see the Bank bring forward its anticipated timing for raising rates.

Graph 2: Australia – Measures of underlying inflation

Year-on-year growth

RBA cash rate guidance

Governor Lowe has previously stated that the RBA Board will be cautious with its response to higher inflation, emphasising that it “will not increase the cash rate until actual inflation is sustainably in the 2–3 per cent target range”. 1 While the phrase “sustainably” in the target range is vague, Lowe has provided some guidance on the conditions in which the cash rate could increase.

- The cash rate is unlikely to increase until underlying inflation is “at least” at the middle of the target band.

- The RBA Board will be using wages growth as one of the “guideposts” for cash rate decisions, with wages growth likely needing to be 3 per cent or higher “to sustain inflation around the middle of the target band.” 2

- The trajectory for inflation will be important, with the RBA likely to respond differently to a gradual increase in underlying inflation relative to a sharp rise.3

- Given the RBA’s outlook for inflation and wages growth at the time of its November Statement on Monetary Policy, Governor Lowe did not expect these conditions to be met this year, with rates expected to be on hold until at least 2023.4

Market and economists’ cash rate outlooks

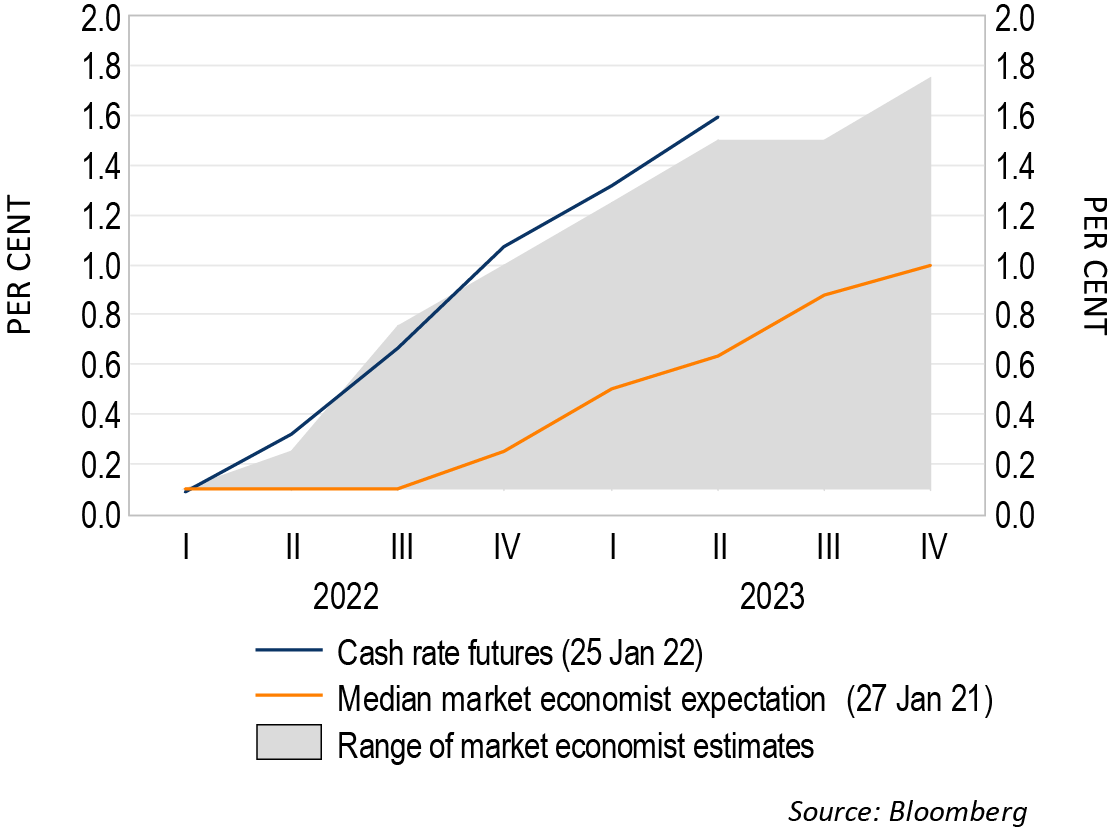

Financial market investors and economists have a different view on the timing of cash rate increases to the RBA (Graph 3). This divergence is most apparent for investors, where cash rate futures imply that the initial increase will be in June this year, with a further rise by August.

Surveys of market economists imply a later timing for cash rate increases than investors. Around a third of market economists expect the cash rate to have increased by the September quarter, with a further third expecting an increase in the December quarter this year. The majority of the remaining respondents expect an increase in the first half of 2023.

There are a wide range of estimates for the trajectory of the cash rate following its initial increase (Graph 3). Market economists expect the cash rate to be between 0.1 per cent to 1.75 per cent by the end of 2023. Cash rate futures suggest the path for rates will be higher, with futures currently around 100 basis points above the median market economist estimate for mid-2023 and slightly above the highest economist estimate for this period.

Graph 3: Outlook for the cash rate

Alternative paths for the cash rate: Model-based scenarios

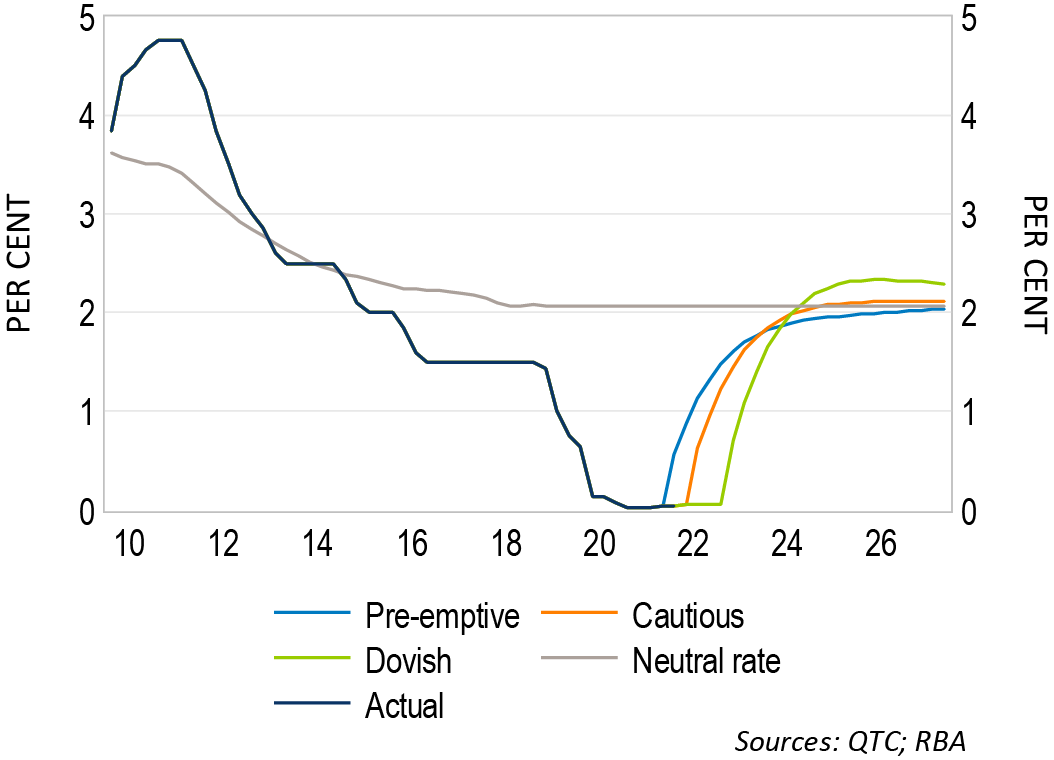

The wide range of cash rate expectations reflects uncertainty around both the economic outlook and how the RBA will respond to this. Given this uncertainty, I have used a modified version of the RBA’s MARTIN model to gauge the sensitivity of the outlook to three different scenarios.6 These scenarios vary in how the RBA initially responds to inflation and wage outcomes. For further details on the scenarios, see the technical appendix.

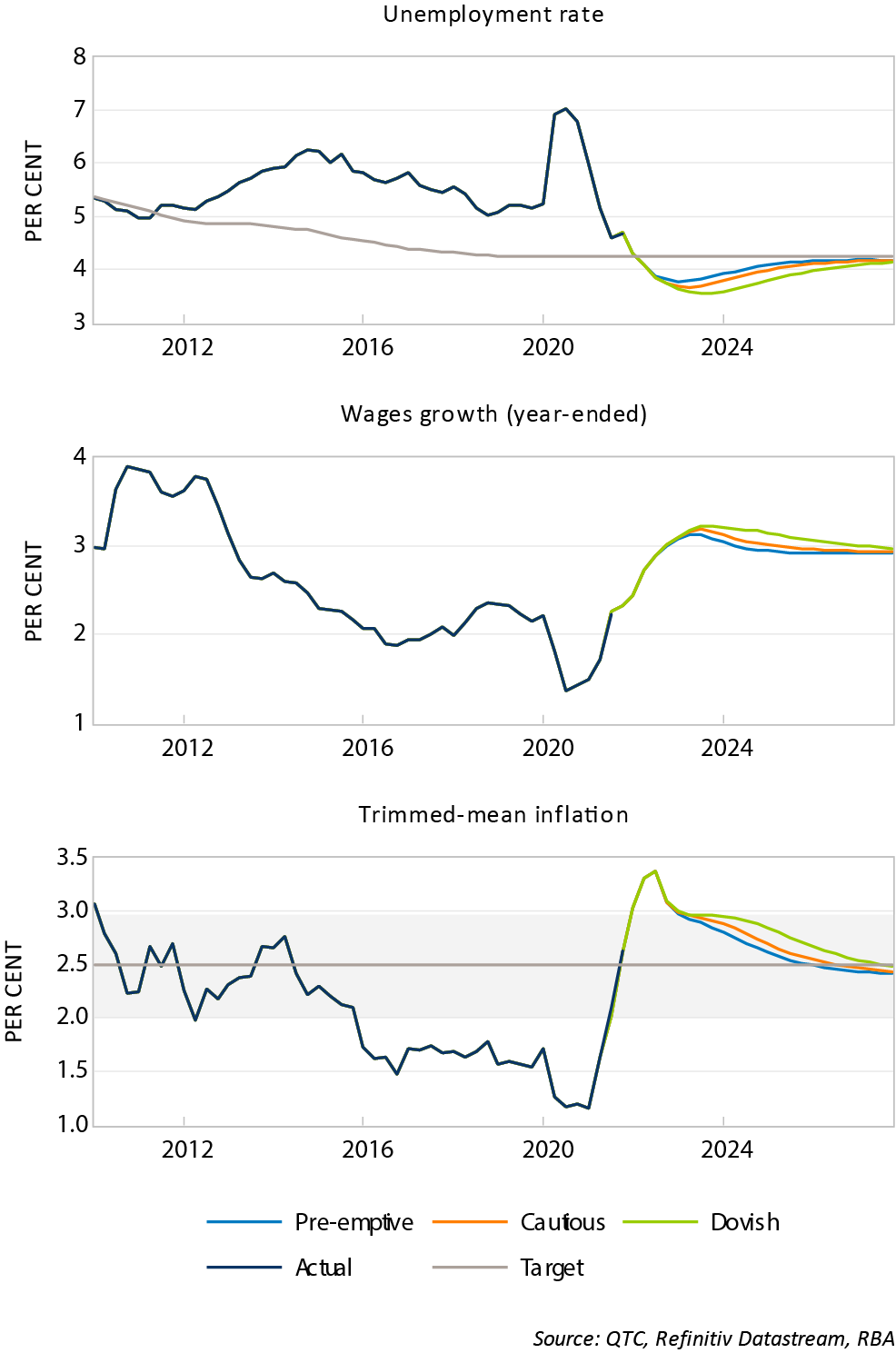

Both the ‘pre-emptive’ and ‘cautious’ scenarios support the view that the cash rate will increase this year, while the ‘dovish’ scenario has the initial increase in the first half of 2023 (Graph 4).

- The ‘pre-emptive’ scenario sees the cash rate increasing in March quarter 2022, following the increase in underlying inflation to 2.6 per cent in the December quarter. This hike occurs with the unemployment rate at 4.2 per cent and wages growth at 2.3 per cent. While historically you would expect the cash rate to be higher under these conditions, a hike at this point is unlikely given the RBA’s current guidance.

- The ‘cautious’ scenario sees the initial hike occurring six months later in September quarter 2022, following three consecutive quarters of underlying inflation above 2.5 per cent. At this point, underlying inflation is 3.3 per cent, the unemployment rate is 3.9 per cent, and wages growth is 2.7 per cent. This is a strong combination of results and it is reasonable that the RBA would start to increase rates in this scenario.

- In the ‘dovish’ scenario, the cash rate does not start to increase until June quarter 2023, following two consecutive quarters of wages growth being at least 3 per cent. At the time of the initial hike, underlying inflation has been above the middle of the target band for 1½ years and the unemployment rate is around 3.5 per cent. The delay in initially increasing the cash rate means that the RBA needs to ‘catch up’ when the hiking cycle starts. This results in both a faster pace of cash rate increases and a higher terminal rate, relative to the other scenarios.

Graph 4: Model based scenarios

Based on these projections, there should be sufficient evidence that inflation is ‘sustainably’ within the target from the second half of this year. By August 2022, there would have been three consecutive CPI releases with trimmed-mean inflation above 2.5 per cent and two releases with it at or above the top of the target band. The unemployment rate is also expected to be at its lowest level since the 1970s. While wages growth is not expected to be 3 per cent at this stage, continued strength in the labour market and the momentum in inflation and wage outcomes should alleviate any concerns the RBA has about the persistence of these improvements. This lends support to the ‘cautious’ scenario and market economists’ expectations for cash rate increases.7

The pace of cash rate increases is relatively swift following the initial hike in rates under all scenarios, due to continued strength in the labour market and higher inflation. For example, the unemployment rate troughs at 3.7 per cent in the ‘cautious’ scenario and remains below four per cent through to the end of 2024 (Graph 5). The low level of unemployment supports both stronger wages growth and inflation, with trimmed-mean inflation remaining above the middle of the target band through to 2025.

Graph 5: Economic projections

Despite the different timing of the initial hikes, the economic outlooks are similar across the three scenarios. This is because the later timing of the initial hike is largely offset by a faster pace of cash rate hikes when they occur. Taken at face value, this suggests that the timing of the initial cash rate increase may not be that important for economic outcomes. If the RBA delays the initial increase by a few quarters, it can compensate for this by having a faster pace of cash rate increases. This illustrates the importance of looking beyond the timing of the first cash rate hike and considering how the tightening cycle might evolve in a broader sense. However, it is important to note that a ‘catch up’ strategy from the RBA might not be so simple. While it might be possible to delay rate hikes for a short period of time, increasing the cash rate either too early or too late is associated with several risks.8

Summary

The different outlooks for the cash rate are summarised in Table 1.

Cash rate futures suggest that the initial hike will be in June this year, while the RBA’s most recent comments suggest this will not occur until 2023 at the earliest. Projections from a modified version of the RBA’s MARTIN model support the view that the cash rate will increase in 2022, with conditions likely to be strong enough to justify a rate hike from the second half of this year. Given the strong momentum in the economy though, there is a risk that the cash rate could increase earlier than this. The scenarios suggest that the RBA may need to increase the cash rate relatively swiftly when the hiking cycle starts, particularly if it delays its initial response to stronger economic outcomes.

A key source of uncertainty for the outlook is the potential effect of the Omicron outbreak (or any future variants). My estimates assume that we reach the peak of this outbreak soon and that the economic implications are limited, but there is a risk that the economic effect could be larger and longer lasting than currently expected. If this were to occur, then the initial hike in rates would be delayed.

Table 1: Model based scenarios

| Cash rate level |

||||

| Initial increase | 2022Q2 | 2023Q2 | 2024Q2 | |

| Cash rate futures (25 January 22) | Q2 2022 | 0.32 | 1.60 | -- |

| Zero-coupon forward rates (31 December 21) | Q3 2022 | 0.34 | 0.98 | 1.66 |

| Market economist median (27 January 21) | Q1 2023 | 0.10 | 0.63 | 1.5 |

| Model scenarios | ||||

| - Pre-emptive | Q1 2022 | 0.87 | 1.60 | 1.86 |

| - Cautious | Q3 2022 | 0.05 | 1.45 | 1.92 |

| - Dovish | Q2 2023 | 0.05 | 0.70 | 1.84 |

Footnotes

[1] Lowe (2021), “The RBA and the Australian Economy”, Address to CPA Australia Riverina Forum, 16 December 2021

[2] Lowe (2021), “Recent Trends in Inflation”, Address to the Australian Business Economists (ABE), 16 November 2021

[3] Lowe (2021), “Recent Trends in Inflation”, Address to the Australian Business Economists (ABE), 16 November 2021

[4] For example, Governor Lowe stated that “the latest data and forecasts do not warrant an increase in the cash rate in 2022. The economy and inflation would have to turn out very differently from our central scenario for the Board to consider an increase in interest rates next year.” He also noted in the Q&A for this speech that an increase in the cash rate in 2022 is a “very, very low probability”.

[6] For a description of the RBA’s MARTIN model, see Ballantyne et al (2019). The modified version of MARTIN that I used for this project is largely based on publicly available code provided by David Stephan at The World Bank (available here). These cash rate projections are estimated using estimating using ‘optimal control’, which estimates cash rate path that minimises deviations from the RBA’s targets for inflation and unemployment.

[7] The ‘pre-emptive’ and ‘dovish’ scenarios seem less likely. The timing of cash rate increase in the ‘pre-emptive’ scenario could be justified based on the economic projections, but it is unlikely the RBA will increase the cash rate this early given its current guidance. In contrast, the ‘dovish’ scenario is consistent with the RBA wanting to see wages growth at three per cent before increasing rates, but it is difficult to see the RBA waiting this long to increase the cash rate given the strength of the inflation and unemployment rate forecasts.

[8] These risks include the potential implications for inflation expectations, housing market conditions, and in the case of hiking too early, disruptions to the economic recovery.